Taking Lines

by Douglas Brooks

For the last year, I’ve been having an interesting correspondence with Josef Eggert of Los Angeles, a former apprentice who I believe found me via the lofting page on my website. I often loft boats for amateur boatbuilders on sheets of large format paper. Lofting is the first step in traditional boatbuilding, a method of deriving fair and accurate patterns for building molds. Its use overlapped the former method of designing and building boats and ships from half models carved of wood. While I loft boats from a designer’s drawings (specifically, their table of offsets), it is also possible to measure an existing boat and record its measured shape. This is called taking lines. In my early work for museums, I’ve measured many boats, including helping measure the lines of the 220' three-masted lumber schooner CA Thayer at the maritime museum in San Francisco.

Josef remembered a favorite rowing boat from his days in Rockland, one he said was built largely by eye, modified from an L. Francis Herreshoff 17-foot rowboat. Josef had donated the boat to the Apprenticeshop but decided he wanted to document its shape for future reference. We worked out a schedule coinciding with the Apprenticeshop’s summer break and met in Rockland.

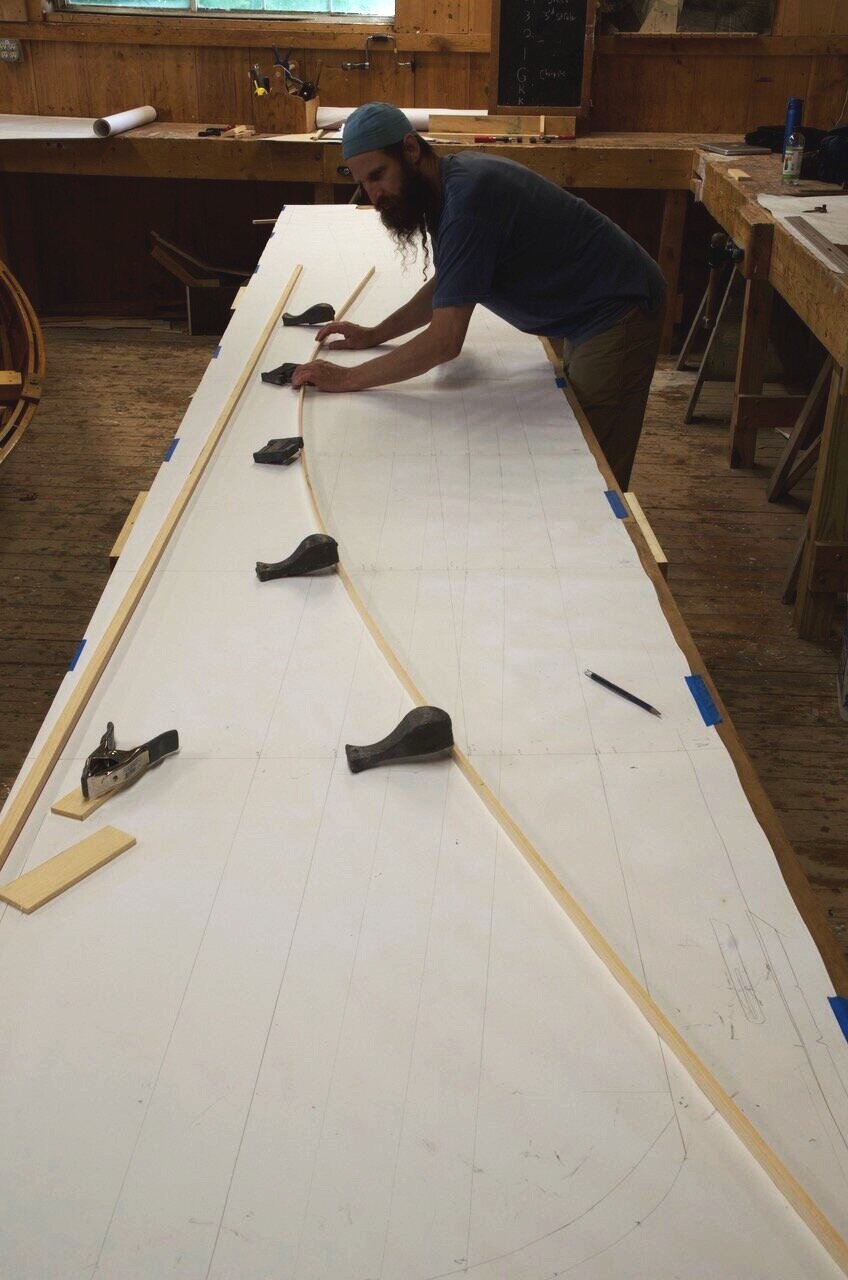

I like to loft small boats on a table. Standing is far more comfortable than working on the floor. I use a series of hollow core doors as a table, carefully cleated together so that they will lay flat atop sawhorses.

After setting up the lofting table, we rolled out the paper and established a baseline along one edge. We carefully placed the centerline of the boat above the line. We then marked off sections square to the centerline two-feet apart, matching the location of the frames in the boat. We would measure the boat at these two-foot cross sections, as well as the bow and stern profiles.

We didn’t use a level on either the table or boat. What we did do was square the boat to the surface of the table. Many boats will show a twist due to age or perhaps dating from their construction. In our case the stem and sternpost were within an 1/8” of each other, a nice break in our favor.

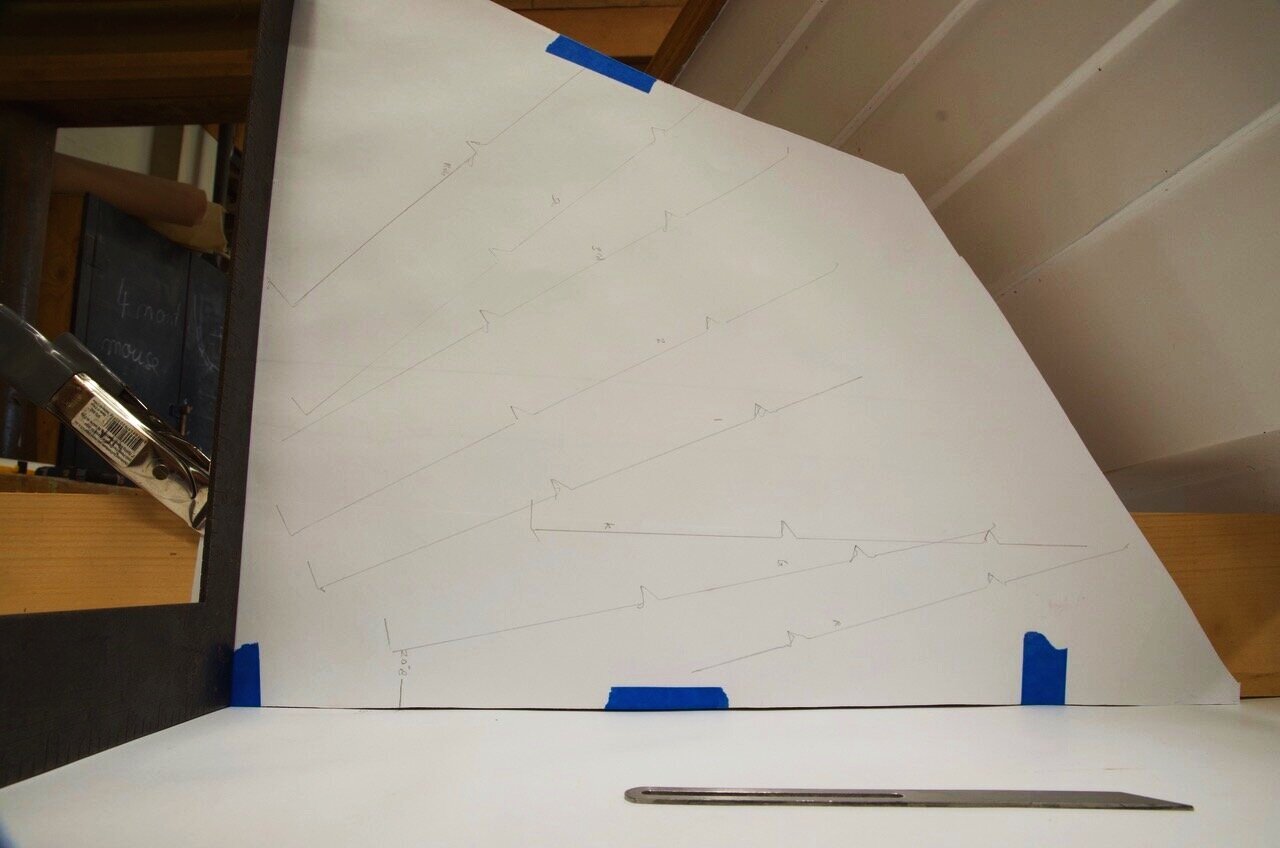

For years, I would measure boats by setting up a right angle, essentially an X and Y axis, and recording points on the hull. Taking a horizontal and vertical measurement to a rounded hull can risk some inaccuracy as the measuring point is meeting the hull at an acute angle. Barry Thomas, the former boatbuilder at Mystic Seaport, published an article describing his method, which in my opinion is far superior. I’ve modified it a bit but basically, Thomas would mount a piece of paper to a plywood backing clamped along the section lines and squared upright. Using a joggle stick, one can touch points on the hull. Meeting the hull at right angles improves the accuracy. Tracing the stick references the point. Not visible in the above photo is a reference line we drew parallel to the centerline 20” from it. Each time we set up paper to measure a section, we marked the point on the paper at the 20” reference line. We also took measurements at each lap, so in addition to getting the hull shape, we also recorded how the planks are lined off, a big time-saver if Josef decides to build this boat.

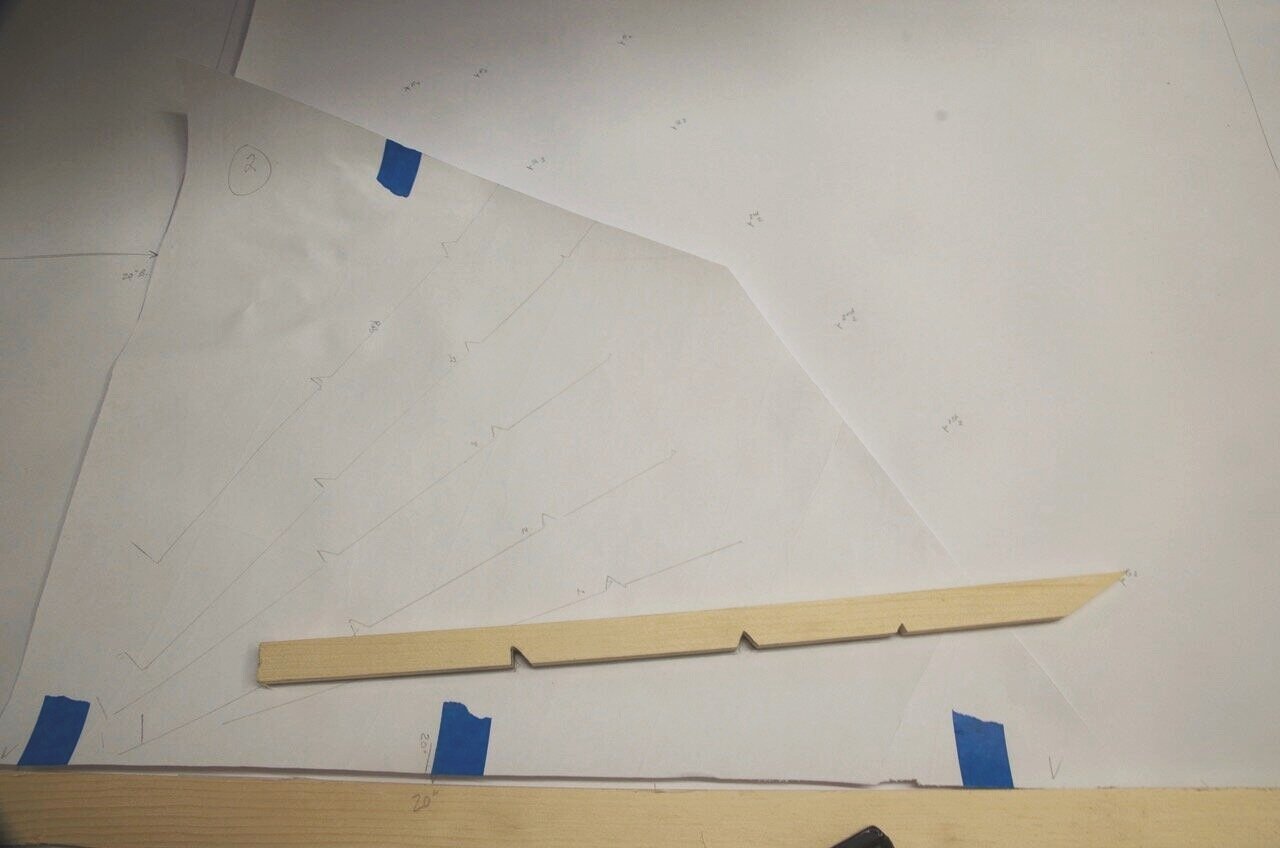

The 20” reference point is visible at the bottom left edge of the paper. The joggle stick tracings are carefully labelled showing what plank they represent. The metal blade of my bevel gauge was used where there wasn’t room to fit our joggle stick. The notches in the stick ensure that we orient it correctly at our next step.

A shot of Josef using the small blade to record under the hull. The boat was blocked up on a pair of 4 x 4s to give us some room to work underneath.

Josef recording the shape of the stem face. He also slid the joggle stick alongside the stem to record the rabbet line at each plank lap. At this point, the piece of paper was crowded with marks, so good labeling is extremely important.

A look at our setup. Josef has just drawn a new centerline along the right edge of the paper and we are starting to loft the lines of the boat.

We lay each sheet of paper down on our lofting, referencing its bottom edge along our baseline and aligning the 20” reference mark with a point 20” from our vertical centerline (we are now working in a sectional view of the hull). The stick is laid back on each tracing and the point is marked. You can see the series of points lie in the cross-sectional shape of the boat at that station. We then take a thin batten and lay it on these points and draw the shape.

From our sections we can get heights and half-breadths that allow us to start drawing the boat full-size in profile and plan views. We’ve removed the boat and Josef is setting a batten along a plank line. For this boat, rather than lofting true waterlines and buttock lines (vertical and horizontal planes of the hull), we lofted the plank laps. It does the same thing, fairing and checking the accuracy of our sections shapes. In this case, none of our points were off more than an 1/8” and most were exactly right. This lines-taking method really offers astounding accuracy. When we were done, Josef rolled up the lofting to take home. He can later convert it into a scale drawing or at any time use it to build a replica.

Douglas Brooks is a boatbuilder, writer, and researcher. He last wrote for this blog about his trip to Japan in November of 2019. You can learn more about his work at www.douglasbrooksboatbuilding.com.